What became of Gurkha, the fearless cult hero…

Pontypridd hooker Phil John, hugely popular with the Sardis Road faithful and one of the finest rugby players never to be capped by Wales, has been interviewed by Media Wales correspondent Simon Thomas…

So, first things first, let’s start with the nickname. Why Gurkha?

“Well, Gurkhas are small and fearless, ain’t they,” replies Phil John.

“I think it was the Chief that came up with that name and it just stuck.”

It’s a pretty appropriate one, as the cult-hero ex-Pontypridd hooker was certainly fearless.

He never took a backward step, as famously illustrated during the Battle of Brive, and it made him hugely popular with the Sardis Road faithful.

It also took him to the brink of a Wales cap, only for his hopes to be dashed by a moment of madness he struggles to explain to this day.

Having started out at Merthyr RFC, from where he won his Wales Youth cap, John joined Pontypridd at 19 in 1982.

“The club was going through a rebuilding process, so we took a bit of a battering in my early days, a few pastings,” he recalls.

But, with the arrival of the Jones brothers – Clive and Chris – as coaches in 1987, so fortunes changed.

“They turned the club completely on its head,” said John.

“They took us from a bit of a laughing stock to a side to be reckoned with.”

Forwards coach Chris Jones had famously been banned for life twice for his indiscretions on the field with Treorchy and he instilled an uncompromising approach.

“We all knew about his reputation about being sent off and going up the mountain and this and that,” said John.

“What I got from him was he would tell you the truth.

“You’d come off knowing you didn’t have a good game, but trying to convince yourself you did, and he’d say ‘You were terrible, terrible. You were dreadful’.

“What he wanted off us was physicality in every game.

“He went out and got the likes of Adrian Owen, who was renowned, Mac Knowles, Denzil Earland, Jim Scarlett.

“These were boys who were up his street. He loved them because there was only way they could play.

“He wanted to make us fearless, so sides didn’t want to come to Ponty, didn’t want to play us. So when they did come there, they were half beaten anyway.

“Training nights were worse than a game. We didn’t hold back. There would be so many boys going down to Ponty Hospital to get stitched up after training.

“Our game was rucking and there was no holds barred.

“We were renowned for being ruthless on the field. Possibly that’s where the House of Pain might have come from.

“At the time, I just wanted to win, but I have seen the old tapes and, looking back on it now, even I’m cringing the way we ran over people. You think ‘Were we really like that?’

“You would just run in and, if they were on the floor you rucked them out of there. If it was the head, it was the head.

“It was allowed in them days. You would have your linesman on one side and their linesman on the other and you just got away with it.

“Today now, I wouldn’t have a career, I think half the side wouldn’t have a career because we’d be cited every week.

“I’d run out and give my opposite number the old ‘Come on then’, just to put the fear of God in him.

“I wanted that little bit of reputation, so it would proceed me. I wanted hookers to worry about me.

“That’s what was instilled in us. We had people talking about us, maybe for the wrong reasons, but they were talking about us.”

And people began talking about John in international terms, with Wales B honours coming his way and then a call up to the bench for the England game during the 1989 Five Nations.

So what recollections does he have of that day?

“Not going on!” he replies with a chuckle.

“It’s frustrating. You are part of the squad and you aren’t, you are in, but you are not.

“Everything revolved around the first XV.

“I do remember the fantastic feeling coming in on the bus and seeing all the supporters. I remember that vividly.

“As for the game, I remember Mike Hall scoring, but it was too much to take on in one.”

Of course, in those days, replacements only came on in the case of an injury, so there was to be no cap, with starting hooker Ian Watkins seeing out the duration of Wales’ 12-9 win.

“There was one incident where he made a break and turned his back,” recalls John.

“The full-back was lining him up and I was thinking he is going to take his kidneys out here.

“It’s an awful thing to say, but I was like ‘Go on!’

“But then the ref blew and the full-back pulled out.”

John was very much in the international mix now though. He was called up by the Barbarians for their Easter programme and even received a letter enquiring about his availability for that summer’s Lions tour of Australia.

In the end, he travelled to Canada with Wales for what was an uncapped B tour, but his trajectory was on the rise.

So much so that he was selected in a World XV squad for a trip to South Africa in August 1989 to mark the 100th anniversary of that country’s Rugby Union, with two Tests arranged against the Springboks in Cape Town and Johannesburg.

“My missus said to me there’s a Mr Willie John McBride on the phone,” he recalls.

“I said don’t take no notice, it’s one of the boys, so I put the phone down.

“He phoned back and said hello and it was Willie John! He was our manager.

“When someone of his stature talks to you personally, calling you Phillip, it’s a special moment .

“He said ‘Would you like to come?’. My first reaction was ‘How do I get there?’

“It snowballed from there.”

John found himself rubbing shoulders with the likes of Phillipe Sella, Pierre Berbizier, Mike Teague, Peter Winterbottom, Denis Charvet and Tom Lawton, along with such established Wales stars as Bob Norster, Robert Jones, Mark Ring, Mike Hall and Tony Clement.

“I am just from Quakers Yard, a small town boy,” he says.

“Then you are in a squad with these people I was watching on the telly the year before, heroes of mine. These boys were monsters to me.

“You got out there and they shook your hand, it was fantastic.”

It wasn’t a trip without its controversy, amid criticism of it going ahead against the backdrop of Apartheid.

“I remember we had a bit of nonsense from party political people who didn’t want us to go,” says John.

“There were tacks on the field and people with banners.

“But I’m not a political person. To me, it was just another step to getting my cap.”

That cap looked to be coming ever closer when he was included in the Wales squad for the autumn Test against New Zealand and, as the year neared its end, he had high hopes of being involved in the 1990 Five Nations.

But then came the incident that was to wreck his chances.

It happened in the Boxing Day match against Cardiff at the Arms Park when he was facing his Wales hooking rival Ian Watkins.

“There had been a lot of press before that game,” he says.

“All week, it had been building up between me and Ian about the Five Nations coming up.

“Anyway, it was a lineout in front of the main stand.

“I looked where Derek Bevan was, he was right at the back, and, as Ian was throwing the ball in, I stuck the head on him. Why, I don’t know.

“It was just one of those mad moments I had, to be honest.

“I look back on it quite a lot and I don’t know how it got into my head.

“I liked to give it, but I would always stand toe to toe. It was just one of them reactions.

“Why I did it, to this day, I don’t know. I must have had a head freeze or something.

“I think it was the build-up. I genuinely thought at the time I was better than him. I believed I was the best in Britain.

“Things were going well for me, I had been on the bench for Wales, there was the Lions letter, the World XV, I was always in the Football Echo.

“Derek didn’t see it, but the whole stadium did.

“It was the Arms Park, Boxing Day, a full house and the whole crowd went nuts.

“I had the ball and Ian came over the top and gave me one. Derek saw that and sent him off.

“I went into the clubhouse after and he was sitting by John Ryan and Jeff Squire and I thought to myself ‘Well, I’m done’.

“Everyone just seemed to drop anchor on me.

“Going into that match, everything was flying for me. The papers were talking about me. Every game I was playing for Ponty, I seemed to be headline man.

“Then I blew it all. I have had to live my life with it since.

“That one error on Boxing Day just flattened my career.

“I never really had a look in again.

“No-one would touch me. No-one wanted to know me.”

But one place where he was still wanted was Sardis Road and he went on to share in Ponty’s league and cup triumphs of the mid-1990s.

“It was like a second coming for me after the kick back,” he said.

“I thought ‘Take that cap out of your head and just get on and play your rugby’ and I thoroughly enjoyed it.”

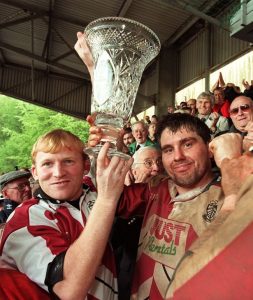

The high point was the Swalec Cup final victory over Neath in 1996, as Ponty made amends for the previous season’s defeat to Swansea.

“The year before, we had a piper taking us to the ground, this and that,” says John.

“We overbuilt it.

“With the Neath game, we didn’t go down the night before, we just took it as a normal Saturday and we went on to have a famous victory.

“When we went up to get the cup, you looked down and you will never see sights like that again for a club match.

“The pitch was chock-a-block and they were singing and chanting.

“I’m getting goosepimples now thinking about it.

“We had to do the dignitary work, but we couldn’t wait to get back to the supporters. They were our friends. We had a connection with them and it was so important.

“You would ask junior clubs who they want in the cup and they would say Ponty because they bring six buses with them. The fans would travel everywhere.

“On match day, I would get a bus down to Ponty train station and it would take me an hour to get to the ground because people would want to shake your hand.

“You couldn’t get a ticket in the end. It would be chock-a-block.”

The season after the cup glory brought the league title.

“We won 20 out of 22 games. That takes a lot of doing, but we had the players,” says John.

“We became the perfect storm.

“We went through thick and thin together and eventually we won the league and the cup and not many people do that. They were fantastic days.”

Then came Europe and a story that is etched in Welsh rugby folklore – the Battle of Brive.

It was September 1997 and Ponty had travelled out to France to take on the reigning Heineken Cup champions.

“Brive had a reputation,” explains John.

“Cardiff had gone there the year before and been bullied, even out in the night.

“You can’t do that to Ponty. We had too many characters who had been there a long time and worked hard for their reputation.

“We went over to Brive and said ‘Right, we’re not taking any of this nonsense off them’.

“I was the senior man and, before we left the hotel for the ground, Eddie Jones (team manager) asked me to give a team talk.

“We went into the room, the coaches went out and I gave a bit of a speech.

“I just said how people would be watching us back home on telly, to remember where we come from, who we are and that we are not taking any nonsense, so to get our heads screwed on.

“We got on the bus and there was silence. I thought ‘Yeah, we are up for this’.”

Then came the game.

“We were in the tunnel and they looked over and they were grinning,” said John.

“I looked up as if to say you f*****g grin and you will have one.

“To me, it was the game of our lives.

“The first scrum, they sent one through, I thought here we go.

“But we loved it. Everybody got stuck in. They would score, we would score.

“They couldn’t get rid of us. I think they were a bit shocked because of the rugby we played.

“They thought we were just another team and they would roll us over, because they were flying at the time.

“But they couldn’t get us off their neck. We were like an itch they couldn’t scratch.”

From the outset, it was a simmering encounter.

“There was a lot of niggle going on, a lot of things the cameras didn’t pick up,” said John.

“You would be on the side of a maul and they would come in and short-arm you.

“They knew how to give it in little sneaky ways.

“They would pinch you, gouge you, they would stamp on your ankles or your fingers, they wanted a reaction. .

“Their centre came over at one point and gave me one and ran back. I was never going to catch him, was I?

“That was the type of game. They would come and say ‘What’s the matter?’ and stamp on your foot.

“It just accumulated.”

Then, on 25 minutes, the match exploded into a mass brawl which resulted in opposing back rowers Dale ‘Chief’ McIntosh and Lionel Mallier being sent off.

“We had taken so much in the game, we were fed up with it,” said John.

“You are thinking, this is coming, this is coming, you knew.

“I can tell you now what I was doing, what I said, it’s so vivid.

“I remember the Chief had these blokes on him an the first person in was Nugget (Martyn Williams). The next thing, we all piled in.

“I went on the side with this big fella and he swung, flipping heck, the wind blew me over.

“If he’d caught me, they would have been pulling me from the moon!

“I pointed to my chin, to say come on then, there it is.

“It was the most physical game I ever played in, but I loved it.

“It was the closest you will get to an international outside of Test rugby.

“Don’t forget, it was a good game. The rugby was great.

“Afterwards, their coach came on to me and said to me ‘Do you want to play for us next year?’”

What happened on the pitch was to be a precursor of events in the night, as violence erupted once more between the two sides at Le Bar Toulzac.

“We were having a few beers with them and they said ‘Come with us to a nightclub’.” reveals John.

“They thought they would only take two or three of us. They tried to separate us and intimidate us.

“But they didn’t realise what we were about. The whole f*****g team turned up, didn’t it?

“Anyway, one of their players lobbed a bottle and it all kicked off.

“Certain persons who were with us won’t put up with that.

“It just got sorted out there and then.

“They picked on the wrong boys, to be honest with you, boys that could look after themselves on the field and off the field.

“They tried it on, but second prize they had, second prize.”

That wasn’t to be the end of the matter though, particularly not for John and team-mates McIntosh and Andre Barnard.

“I was rooming with Neil Eynon, as I always did,” he said.

“He answered the door and said ‘’Gurkha’, it’s for you, there’s a fella with a gun.’

“It was this gendarme with a gun across his chest.

“He said ‘No 2?’, I said ‘Yeah’ and he goes ‘Come with me’.

“When I got downstairs, Dale and Andre were already there.

“It was like Michael Jackson had come to town. All the press were there, everybody was there.”

The “Ponty Three” ended up in the Brive courthouse and facing a hearing in front of a judge.

“They handcuffed us, we had no representatives, they were speaking in French,” he said

“The judge goes ‘If I find you guilty, you will do four years’.

“I was thinking ‘Flipping heck, where is this going, this could get serious by here’.

“We looked out of the window and the world’s press was there.

“Dale phoned home and said it was going ballistic back there.”

The trio ended up spending the night in the jail.

“They left the cells open for us and we talked most of the night,” reveals John.

“We got really close. Dale told me about his family and I told my story and Andre told his, we talked about different cultures.

“It was a special night really because I found out things about Dale I had never known, he found out things about me and we just bonded. Me and him are forever on the phone now. We have stayed very close.”

As for why they were the ones singled out, John has his own theories.

“It stemmed from the match with me and Dale because we were the two big hitters on the pitch,” he said.

“They saw us as the two leaders.

“I think with Andre, it was the wrong person picked up.”

The following day, they were able to head home.

“The three of us were on the front of the paper,” said John.

“We got on the plane and everyone was pointing at us. It was the news of the time.

“After that, we had a lot of letters coming to the house. We couldn’t understand them, they were in French.

“We were banned from France for a couple of years and I heard they brought some people over to get us back there, but nothing ever really came of it.”

John left Ponty at the end of that season to spend a year with Exeter, but he certainly wasn’t forgotten.

Phil John acknowledges the Pontypridd fans after the 1996 Swalec Cup final victory over Neath

“For my first two games, there were two buses there from Ponty,” he recalls.

“Rob Baxter, the Exeter captain back then, was saying ‘Is it always like this?’

“I did have a very close relationship with the Ponty fans.

“It’s something you can’t buy, something you will take with you for the rest of your life.”

A former mining surveyor at Merthyr Vale colliery and ex-factory worker, John is now employed by Anco, installing overhead electrification for trains.

“I am almost 60 now and people still remember the glory days,” he says.

“They come on to me and want to shake my hand. It’s really heartwarming.”

It’s safe to say this fearless ‘Gurkha’ left his mark.