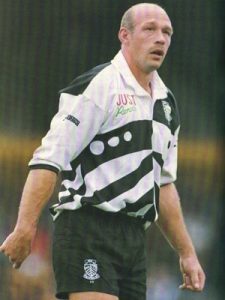

Richie Collins – a man ahead of his time

Former flanker Collins played 28 times for Wales between 1987 and 1995, sharing in the Triple Crown triumph of 1988. He had three spells with Pontypridd RFC, twice as a player and then as coach.

Listening to Richie Collins reflect on his playing career, you come to realise he was very much a man out of his time. With his basketball background, he was blessed with rare skills for a forward in the 1980s and ’90s – the Justin Tipuric of his day. He also adopted a professional approach in an amateur era, with a dedicated focus on fitness and conditioning.

As such, he found himself at odds with the drinking culture of the time and the old school approach to touring.

Now into his 60th year, you can almost sense the former policemen shaking his head as he talks about some of the things he witnessed.

He didn’t take a conventional route into rugby either, only taking up the game in his late teens.

Raised in Grangetown and educated at the Mostyn catholic school in Ely, the Cardiff kid’s sporting attention lay elsewhere when he was growing up.

“There was a teacher at school who was into basketball and he set up a team,” he explains. “I found I really loved it.”

Collins went on to become the youngest Welsh basketball international, aged just 17, and was named Junior BBC Wales sports personality of the year.

So how did the switch to rugby come about?

“I wanted to put a bit of weight on for playing basketball, so my father said why didn’t I pop over to St Albans RFC to train with their Youth team,” he says. “I was about 18 then. Because I always kept myself fit and I was deceptively quick, they said do you want to play and I said ‘Yes’.

“They said ‘What position do you play?’ and I said ‘I don’t know’. I had no idea. My dad said I should play flanker, so I did.

“I remember my very first game for them was against the CIACS and I was basically asking other players ‘Where should I go now? What do I do?’ That’s how little rugby knowledge I had.”

But it soon became apparent he had a real talent for the sport, aided by his grounding in basketball.

“It certainly benefited my rugby,” he said. “As my career progressed, it became apparent a lot of the skills you learn in basketball are very useful in rugby. I watched the replay of the Wales-Scotland game from 1988 when it was on the TV not long ago and, as I was getting tackled, I did one of these passes out of the back of the hand.

“It’s all the rage now. That’s what people try to do, but you didn’t see it back then. That only happened because of my basketball. It just came natural from that.”

After starting out with Pontypridd, the young Collins had a couple of spells playing in New Zealand with the Johnsonville club in Wellington.

“It was an excellent experience out there, it really was,” he said.

“One of the first things I learned was don’t lie on the wrong side of the ball because you will get a hell of a kicking!”

On his return home, he linked up with Newport, playing 104 games for the Black & Ambers between 1983 and 1986.

“I had four cracking seasons with them when Charlie Faulkner and Roy Duggan were the coaches,” he said. “I very rarely missed a game.”

His fine form on the openside saw him selected for Wales B, including the 1986 tour of Italy.

Then, on joining the constabulary, he switched to South Wales Police RFC and it was from there he made his Test debut against England in the infamous 1987 Five Nations match in Cardiff. Named among the subs, he found himself coming on to win his first cap after just a couple of minutes when Phil Davies had his cheekbone broken by a punch from Wade Dooley.

“I don’t think we’d had time to unwrap any of the sweets!” he recalls. “We sat down and next thing I know I was getting shouted to get changed to go on. It was that quick.”

After sharing in a 19-12 victory, he made his first start against Ireland the following month and then came that summer’s inaugural World Cup out in New Zealand and Australia, where he wore No 7 in the wins over Ireland and England, as well as the semi-final against the All Blacks.

“Nobody knew what to expect or how to approach it,” he recalls. “I remember us flying out to New Zealand and being on the same plan as the Irish team. We had a stopover at one point. We were sat down having coffees and the Irish were running on the spot and doing press ups. We were looking a bit bemused and wondering what the hell was going on!”

What also sticks in Collins’ mind is how differently Wales approached the tournament compared to the host nation.

“Having played out in New Zealand, I already had an inkling of how far ahead they were in the way they trained and prepared for matches,” he said. “It was light years ahead of us in Wales. So I always knew the All Blacks were going to be super-prepared.

“Even though the game wasn’t professional, New Zealand treated that tournament like a professional team would. We treated it sort of like an end-of-season tour, which summed up the difference between the nations. One decision I could never work out was what happened between the quarter-final and the semi-final, which was just six days later.

“We beat England in the quarters in Brisbane and we all had a great drink, as you did in those days, and then the next day we got on the bus and went up to Surfer’s Paradise and basically we were told we had three days off to do whatever we wanted to do. So you can imagine what happened then!

“Then we got back and started preparations for the semi-final against New Zealand (losing 49-6). That summed up for me the Welsh attitude at that time. I never fully understood that. I know for a fact the All Blacks players certainly weren’t doing that. No way.”

Collins continued: “Whenever I went on tour with Wales, it always seemed to be very much like an end-of-season tour. One thing I struggled to do was do a fair bit of drinking and then be able to train or play. I just couldn’t do it and I wouldn’t want to do it.

“I prided myself on my fitness and I wanted to go out and do the best that I could without having a load of beer on board.

“I always think to myself how good we could have made those tours, playing-wise, if the Welsh set-up treated it like New Zealand treated it. The tours themselves were always great to go on. I just wish we had approached it in a more professional attitude.”

It was much closer to home that Collins enjoyed the high point of his Wales career, as he played a key role in the Triple Crown triumph of 1988, starting all the games in that season’s Five Nations. With the team’s expansive approach, he was the perfect link man, as illustrated by the way he was twice involved in Adrian Hadley’s second try against England at Twickenham.

“Tony Gray and Derek Quinnell were excellent coaches and that’s how they wanted to play,” he said. “They wanted every player to express themselves and for us to play an open game and that suited me down to the ground. We had so many skillful players. Jiffy was probably the best outside-half in the world at that time. Some of the things he did were absolutely incredible.

“You had Mark Ring, who had no fear about trying things either, Bleddyn Bowen was a steadying influence alongside him and then you had Ieuan on the one wing, Adolf (Hadley) on the other and Tony Clement at full-back. You had fantastic players there. Why wouldn’t you try and play rugby with that sort of back line? And that’s what Tony and Derek wanted to do, play rugby. We scored some fantastic tries.

“The Scotland game is the one that really stands out. Going to Twickenham at that time held no fears for me. The Scottish team were good with a number of fantastic players in their set-up. The way we fought back to win after falling behind in that game was the memorable thing. We played good rugby as well.

“It’s got to be up there because of what we achieved that year. It was just a pity that way we were going ran its course.”

That summer, Wales came down to earth with a bump as they toured New Zealand and were thumped by the All Blacks in the two Test matches, losing 52-3 and 54-9.

“Whoever agreed to the itinerary on that tour needed shooting,” said Collins. “It’s always going to be tough in New Zealand, but it was just relentless. We went Waikato, who were provincial champions, Wellington, Otago and then into the first Test in Christchurch, so four massively tough games. Then before the second Test we played against Taranaki who had just been told to kick seven bells of crap out of us and that’s what they proceeded to do.

“That itinerary would be a hard ask for a Lions trip. So to send us out there like that, especially as New Zealand were far and away the best team in the world at that time. They were the best prepared, the best organised.

“And the booze factor came into it again with us. Just before the Waikato game, it was one of the boys’ birthdays. They said go and have a couple of beers to celebrate and a number of the players had far more than a couple.

“Anyway, we were beating Waikato and then in the last 25 minutes, they got on top and won and I have no doubt that came back to the alcohol thing. I just can’t get my head round it now and I certainly couldn’t get my head round it then. I don’t mind having a drink, but if you are representing your country, do it when the job is done, not when you are leading up to doing it.

“It’s strange, but there we go. That just reflected where Welsh rugby was compared to the likes of New Zealand and Australia. They were light years ahead of us in how they were approaching rugby. It was still amateur and we were approaching it as amateurs whereas these countries were approaching it far more professionally, especially at international level.”

The real low point came with Wales’ 1991 tour of Australia, under the coaching of Ron Waldron.

“That was a disaster from the start,” said Collins, who, by then, had joined Cardiff. “Right from the outset, you could sense it was going off the rails a bit. I missed the start of training because I’d booked a holiday for two weeks, not having had a letter asking if I was available. When I got back, I went down to Sophia Gardens for training and the first person I saw as I got out of the car was Phil Davies.

“I said ‘Have I missed anything?’ And he said ‘No. All we’ve done is run. We haven’t really touched a rugby ball’. We did that again then for another couple of weeks. Then when we arrived in Perth, Ron said ‘Right, the training ground is two miles straight down the beach, I’ll see you there’. So we all had to run to the training ground and when we got there we were told to do five laps to warm up.

“I remember thinking ‘This is crazy’.

“I know all Ron wanted was for Wales to do well. He passionately wanted that, which is why he ended up so ill out there, I think. But whatever advice he was getting on the fitness front, it was certainly the wrong advice. You never had any down from training. We had hard sessions right up to the day before a match, you would travel the next day and when we got to wherever we were going, we would have another hard training session. You were just not getting any recovery.

“Like I say, I always prided myself on my fitness. But I remember thinking one day, ‘I am going to have to pretend I’ve got an injury here because I am shattered, I need a break’. That training regime contributed to what proved to be some very poor performances from us out there.

“There was just no let up and the boys were physically shattered. As a whole squad, we were completely knackered. Of course, it then splintered. There was a large Neath contingent who thought if anything was said about what was going on, we were having a go at Ron and they looked to defend him. It became a bit of us and them.

“I thought it was a bit of a complete over-reaction from some of the Neath boys. I never heard people belittling or criticising Ron as such. It was more how things had gone about. Don’t get me wrong, some of the players didn’t do themselves any favours. The Neath contingent were very committed and wouldn’t go out drinking and then you had other parts of the squad that would go out drinking. As the split became greater, so that became more and more apparent.”

Things got progressively worse on and off the field, with a humiliating 71-8 defeat to New South Wales followed by a 63-6 thumping at the hands of the Wallabies, with the post-Test function culminating in an unsavoury altercation among the Welsh players.

“It was completely and utterly stupid,” said Collins. “I could hear the arguing building up, so I went over. As I got there, I remember something happening between Kevin Phillips and Clive Rowlands (manager). I was saying ‘Woah, come on fellas, calm it down, we are a team here’.

“Next minute, I was in the middle of it and it got a little bit heated between me and Kevin. I was thinking ‘How the hell did I end up here?’ It was a sad old thing to happen. I knew Michael Lynagh and a number of the Aussie lads fairly well through playing Sevens against them all over the world. They were saying ‘What the hell is going on there?’ They couldn’t believe it.

“It wasn’t a good tour for many reasons. It just highlighted how far we had fallen behind organisationally and coaching wise. The national team should never get beaten by any country like that.”

There was further ignominy to follow later that year, as Wales bowed out at the group stage of the 1991 World Cup after losing to Western Samoa on home soil. That was to be Collins’ last game for his country for the best part of three years, as he slipped into the international wilderness.

But a return to Pontypridd reignited his career and, at 32, he was recalled for Wales’ 1994 summer tour of Canada and the South Seas, starting all four Tests.

“We were a lot better prepared on the rugby side, but we certainly weren’t prepared for the heat,” he said. “Against Samoa, our changing room was a big tent and, if it was 100 degrees outside, it was 150 degrees in this tent. It was incredible. It is very difficult to play for 80 minutes in those kind of conditions. That was really hard.”

Collins remained a regular in the Wales team the following season, with his 28th and final cap coming against Ireland in March 1995.

There were still more highs to come on the club scene, as he helped Ponty win the 1996 Swalec Cup, with victory over Neath in the final.

A late career spell with Bristol followed before he hung up his boots in 1998.

Then came a move into coaching, as he headed back to Ponty once more, spending two and a half years in charge at Sardis Road before stepping away from the game in 2001.

“I had been in rugby a hell of a long time by then and never had a break away from it,” he said. “I played for something like 18 years and went straight into coaching, which I thoroughly enjoyed, but I just felt I had to take a break and I took up golf.”

After finishing with the police some 14 years ago, Collins set up a school transport company, specialising in wheelchair accessible vehicles for disabled children.

“I bought a couple of vehicles, got some drivers and it’s just ballooned from there,” he said.

“I was only ever looking to have two vehicles and I’ve got 40-odd now, servicing schools in Newport, Caerphilly and Cardiff mainly.”

Living in Machen, he’s now 59, but he’s still young at heart and still in good shape.

“I still feel about 20,” he said. “I do a fair bit of cycling and I do like the gym. I still like to keep myself fit.”

Collins has now been out of rugby for two decades. So, as our conversation comes to an end, I wonder how he looks back on it all today?

“It’s always nice to talk about what used to go on,” he said. “I wouldn’t change it for the world. It was a fantastic time. It would have been nice to get some of the rewards the players get today.

“I always feel I worked as hard as they do now and I was holding down a full-time job in the police. I think the more professional environment would have suited me, but I was born a bit too early I’m afraid.”

Richie Collins. A man ahead of his time.